One Child

The anthropic principle says that we shouldn’t be surprised by necessary conditions for our existence, because of selection bias: if the conditions weren’t met, we wouldn’t be around to be surprised. The most famous example comes from cosmology, couertesy of Fred Hoyle. In 1952, the only known way of getting elements heavier than Lithium was through stellar nucleosynthesis. However, physicists thought that it was impossible to create elements heaver than Beryllium in stars due to Beryllium-8’s extremely short half-life (6.7e-17) seconds. But, argued Hoyle, most life forms on earth are Carbon-12 based, so there has to be some way to create Carbon-12. It’s far more likely that we’re wrong about the “Beryllium barrier” than it is that the Carbon-12 on Earth comes from some non-star source. So we shouldn’t be surprised to find a pathway, however unlikely it seems, to Carbon-12 through stellar nucleosynthesis. “I exist, therefore the Carbon-12 nucleus must possess an energy level at 7.65 MeV.” Hence, the triple alpha processs.

What works for cosmology also works for demography. Pre-indsutrial societies had very high child mortality. Any society that survived despite this high mortality must have also had a very high total fertility rate (TFR), the number of children born per woman. Therefore, if you’re alive today, your ancestors were almost certainly part of a high-TFR society, and you shouldn’t be surprised to find all sorts of high-TFR beliefs in the past. As a rule of thumb, pre-industrial societies had to have TFRs of at least 5 in order to survive at all.

This observation isn’t vacuous — some past societies did have TFRs below 5. That killed their population growth, and those societies have fewer surviving descendents today. An extreme example comes from 1800s Hungary. From Vasary’s “The Sin of Transdanubia”:

From the late nineteenth century there was a rigorous system of fertility control in certain regains of rural Hungary for which there have been few parallels. The Hungarian ’egy gyermek rendszer’ translates literally as ‘one-child system’. ‘One-child’ because it refers to the practice of couples aiming towards a completed family of one child, whether male or female. ‘System’ because it was not a question of a random scattering of families that, for a variety of reasons, had few children, but a community-wide practicy of rigorously controlled fertility with a comprehensive system of practices and ethos backing it up.

Ansley Coale commenting on the same situation:

The instances of pre-industrial parity-related limitation of marital fertility cited earlier are examples of how such limitations can reduce fertility below the level consistent with survival. In the villages of Baranya, known by their nineteenth-century contemporaries as addicted to the one-child family, in which marital fertility was very low and strongly restrained by parity-related measures, mortality was still high. In Besence and Vajszlo more than 20 percednt of the newborns died before reaching age one until late in the nineteenth century; many of the villages of southern Transdanubia had a negative rate of natural increase as a result of such low fertility while mortality remained high. In the French départements where fertility was already low in the early nineteenth century, the rate of childbearing was not adequate to replace the population. In both Lot-et-Garonne and Calvados, the population declined steadily after 1836, by a total of 20% in one instancce and 25% in the otherk, with no substantial out-migration.

In contrast, Benjamin Franklin estimated that Purtin New England had a TFR of about 8. Others came up with lower estimates, e.g. K.A. Lockridge’s estimate was ≈5, but either way, a one-child policy it was not. The population of the Bay Colony grew from about 20,000 in 1660 to 200,000 by 1760, a growth rate of 2.3% per annum. (Obviously, this was driven partly by immigration, but as far as I can tell, natural increase dominated.)

It’s not surprising that Puritan New England played a bigger role in American History than rural Baranya did in European history, or that more people today are descended from the former than the latter. One is halving every 30 years, and the other is doubling. If you started with 10k people in each society, after 100 years you’d have ≈1k in Baranya and ≈100k people in New England. Simplistically, someone alive 100 years later is 100x more likely to come from New England over Baranya.

So, again, if you’re alive today, then it’s overwhelmingly likely that your ancestors were part of a high-TFR society in the past. And you should expect all sorts of high-TFR beliefs to be prevalent. Examples:

- Prohibitions on contraception.

- Early and full marriage rates. (In China, around 1800, the average age of first marriage was 19 for women, and fully 99% of women eventualy married.)

- Various exhortations to be fruitful and multiply.

- Mencius: “Of all unfilial acts, to have no descendants is the worst.”

- Muhammad: “Marry those who are loving and fertile, for I will be proud of your great numbers before the other nations.”

- From the Manusmriti: “To be mothers were women created, and to be fathers men.”

- Etc., etc.

Again, we shouldn’t be surprised by these beliefs — without them, we wouldn’t be here.

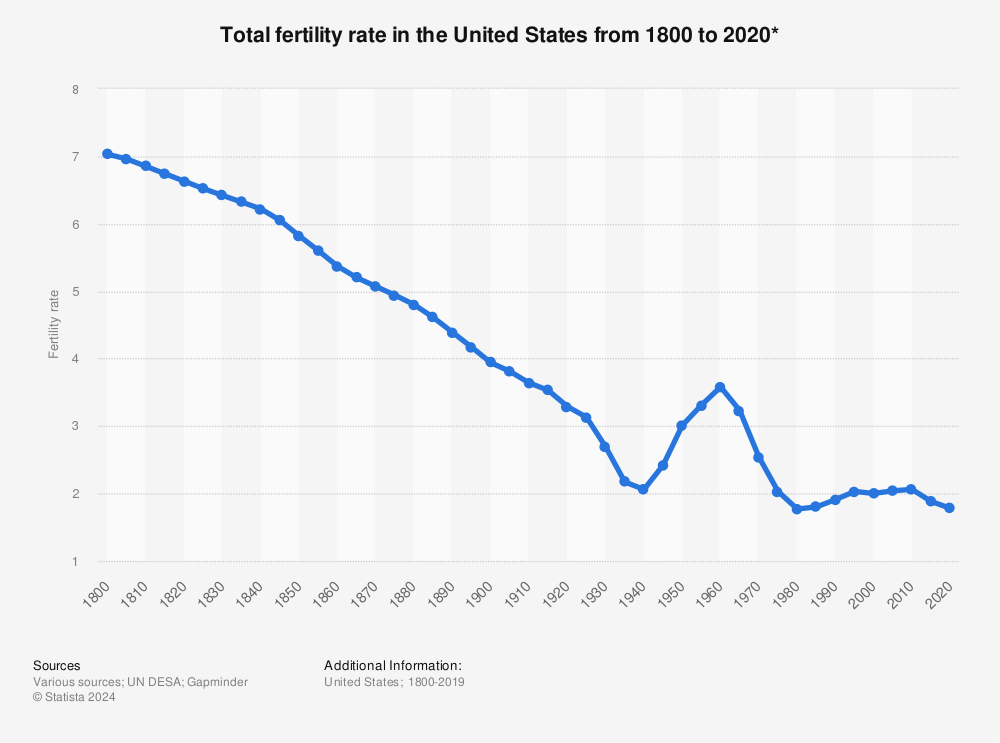

But: obviously things have shifted. Here’s a chart of TFRs in the United states from 1800 to 2020:

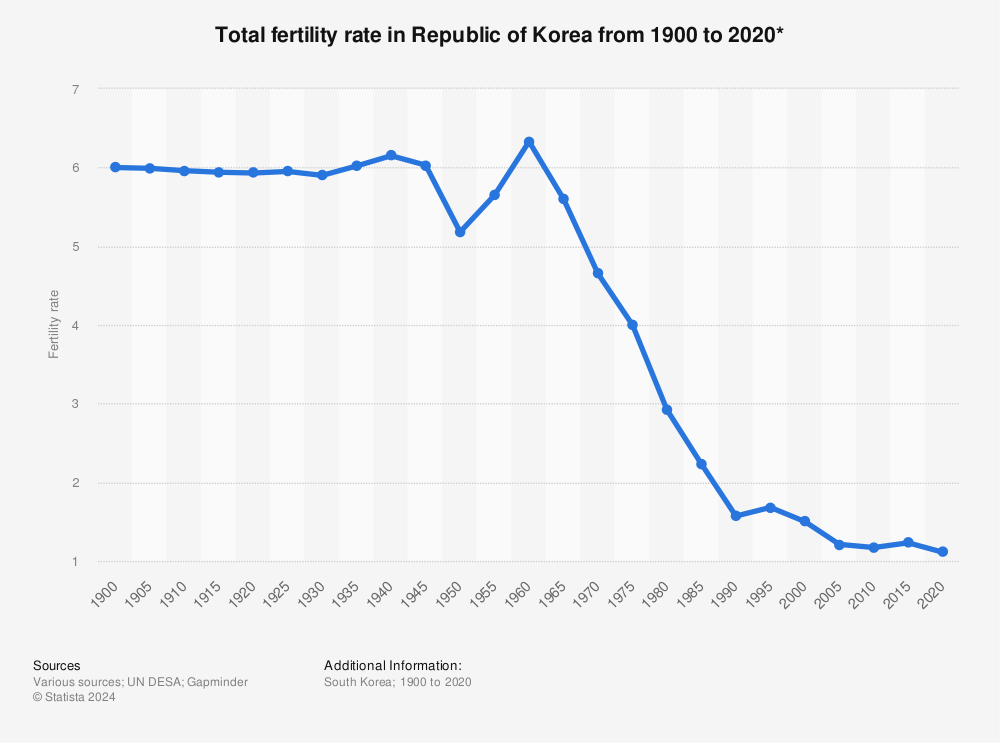

The decline is even more extreme elsewhere. Here’s Korea, for example:

In rich, industrialized countries, modern beliefs are generally not high-TFR beliefs. One could chicken-vs-the-egg this, arguing that the beliefs produced low TFRs or conversely that low TFRs produced the beliefs as cope. And, of course, there’s the argument that some third variable explains both low TFRs and low-TFR beliefs.